A Chronicle of My Life in Service

By Jack London

Contents- THE BEGINNING: Basic Training and the first landing

- COLD MOUNTAIN: Baptism under fire, attack gone wrong

- BANZAI: Terror in the night, the enemy’s mass attack

- BURTON ISLAND: Friendly Fire, turned hostile

- EASTER SUNDAY: A Kamikaze welcome to Okinawa

- HOMEWARD BOUND: The wake of an Atomic Bomb

- PROFILING: My friend Gershon

- EPILOGUE

THE BEGINNING: Basic Training and the first landing

|

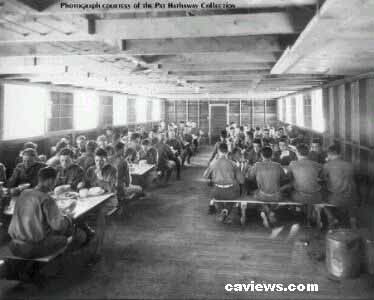

| Troops at Fort Sheridan |

The brief ceremony ushering me into the Army was an emotional moving experience that produced in me a serious patriotic consciousness. The dignified event changed the anguished and somber mood of the other inductees that we were feeling this cold and dreary day. In a short while the tender loneliness that separated us changed, as this gathering of strangers learned how much we shared in common. The induction process continued at Fort Sheridan, north of Chicago on the Lake Michigan shore.

Weather temperature at Fort Sheridan, this first week of January 1943 was very cold, dropping below zero each night. Our billet was a tar- paper barrack lacking insulation and heated by two small coal fired stoves, incapable of supplying sufficient warmth during the day. Each morning I would dress under the blanket, as fire in the stoves was no longer burning.

The induction process included inoculations for disease prevention. Many of the inductees fainted as they watched the hypodermic syringe about to pierce their arm. The induction process ended in three days and we were prepared to leave Fort Sheridan. We boarded ancient resurrected railway coach cars with duffel bags containing our new issued uniforms.

The ride on the train took two days and ending in a railway yard in Camp Wheeler, an infantry-training campground near Macon, Georgia. We arrived at a late hour and glad to be led to a barrack where we could set aside the heavy duffel and contemplate a restful night sleep. It was difficult attempting to sleep on the cold railway coach in the heavy overcoat. In a short while after arrival the lights were turned off and quiet was restored, I was finally able to stretch out in hope of a comfortable night sleep. However, the sleep I was expecting was abruptly interrupted by voices of shouting men and glaring lights that suddenly illuminated the room. I wondered what disaster could have caused such a sudden outburst at this late hour. The explanation given: a soldier in bed on the floor below felt the drip of liquid falling on him from above. It turns out another inductee, sleeping on the second floor, found it easier to empty his bladder at the foot of the bed than try to locate the latrine in the dark and unfamiliar surroundings.

Training began in earnest with calisthenics, then learning to march, and drilling. Taking precedence over the basics was learning infantry tactics, weapons training, and what to do to stay alive. All of this preparedness was completed in eleven weeks of basic training. We were trained as a unit, but then separated, as individuals shipped to existing main line units being assembled throughout the country. Friendships that had been readily formed, were sadly interrupted, most of us never to meet again. Once again I was in a railway yard, boarding a train for an extended six day crossing of the country, ending at Fort Ord, California.

|

| Troops at Fort Ord, California |

I was assigned to the Seventeenth Infantry Regiment, a unit attached to the Seventh Division, which had been a motorized Infantry Division. The Division recently returned from maneuvers in the Mojave Desert, practicing desert warfare tactics. Soon after my arrival at Fort Ord, there was a noticeable increase in activity. Equipment was being collected and packed in preparation for leaving. Many rumors contributed to the excitement of speculating about our destination.

I learned of another soldier of Jewish faith in the adjacent barracks. After making his acquaintance, I realized that he was pleased as I, to find someone who shared the same religious faith. For the celebration of Passover 1943, all Jewish soldiers were invited to a Seder provided by the people of Monterey California. My new friend Gershon and I attended this inspiring event together in the company of 150 other soldiers. I then learned that my friend was an Orthodox Jew.

Though some of our bags were packed, troop training continued. Conditioning included a twenty five mile hike to test our stamina; then a climb to the top of a thirty five foot high platform. The top of the platform was reached by climbing a rope cargo net. The fear of climbing to the top of that platform affected me more that day, than the many ships I would board and leave in the months ahead.

April 22, 1943, was the day my regiment departed Fort Ord, destined to a place not yet revealed. The mood was grim, as we were leaving our comfort zone. It was reasonable to assume that we were being taken to a hostile destination. The train ride was shorter than my previous trips and terminated at the dockside of a large vessel in San Francisco. We were ushered aboard the USS Harris, a naval troop transport. There was no fan fare, no horns, no cheering, hardly anyone to notice our embarkation. It was as though the Army was trying to sneak us out of town.

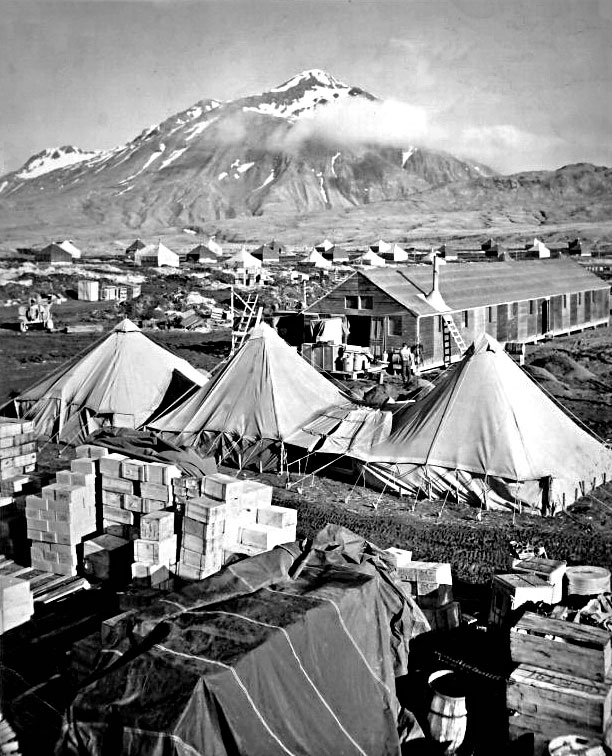

In roaming through this old ship, I saw that it was loaded for combat. Cannons, vehicles and other war material were stuffed wherever there was space. For most of us, travel on an ocean going ship was a new experience and our sea worthiness was about to be tested. The first days of sailing were rough. For some men it would be an unforgettable memory. We were told that we were to attack the island of Attu, and reclaim it from the Japanese occupants. Attu is an island 1000 miles west of the Alaskan mainland in the stormy Bering Sea. Temperature and weather conditions worsened each day as the ship sailed north. It was noticeably colder with mist, fog and low hanging clouds reducing visibility. The sun was not seen on many days. This was not my choice for an ocean voyage.

Disembarking the ship near the invasion site the day first chosen for the landing was delayed. It was impossible to see through the fog. Four days later on May 11, we did disembark, though the fog still shrouded the ship permitting only blurred images and recognition difficult.

The descent from the ships deck into the assembled landing craft, required inexperienced troops to carry a heavy backpack, gun belt two bandoleers of ammunition that crisscrossed the chest and a rifle; using a rope cargo net to get down. The cargo net sagged and tugged with each step as I moved down, trying to avoid intruding on the space of the soldier descending alongside. The disembarkation began at 5:am. We were unaware at that early hour that we would not reach the beach until eleven hours later. An LCVP, flat bottom Higgins boat, with a ramp at the bow would deliver us to the island. The fleet of boats transporting was ordered to circle the troop transport as we waited for the fog to break-up. The exhaust fumes discharged by the fleet of landing craft soon impaired the becalmed air causing many soldiers breathing difficulties. Combining the deafening roar of the many boat engines and having to breathe the foul air changed these once anxious invaders into a wretched sickly assembly hardly suited for this invasion.

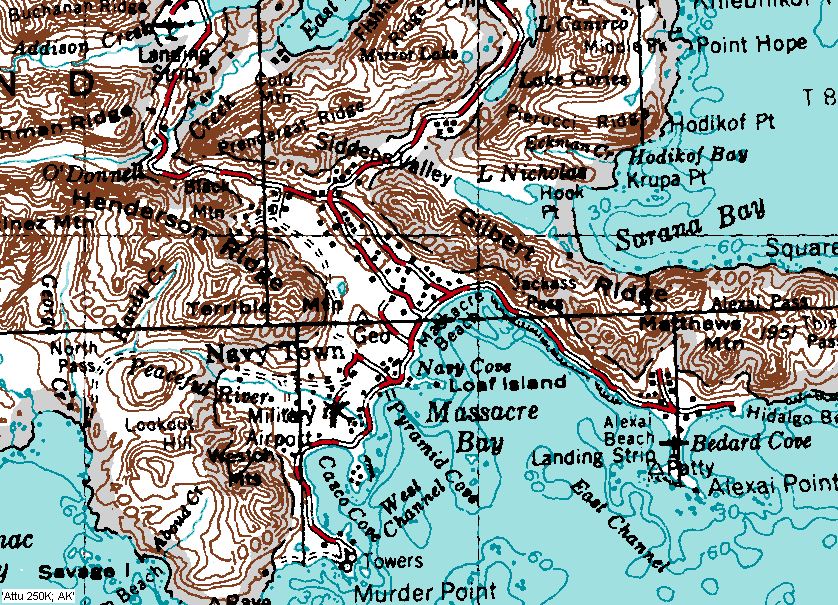

It was late afternoon before a refreshing wind dispelled the fog and permitted the sun to appear. The invasion fleet was finally able to proceed to the beach with a naval destroyer piloting our direction and guarding the approach to the island. The coxswains piloting the landing craft were anxious to be relieved of tending this landing force of stressed-out invaders. We scrambled ashore on a beach without gunfire being exchanged. Massacre Bay was not a fitting name for a peaceful arrival.

|

| Massacre Bay - Americans bring ashore captured Japanese landing boat at Attu |

The occupants secured the entire beachhead without any display of hostility. It appeared as though the front door had been left open for our arrival. We were fortunate to have found this valley accessible to us. An ominous feeling pervaded the platoon, as we felt there could be a price to pay for this good fortune. There was little time left of this day and we hurried off in the direction of our mission outpost. The sight of the snow covered mountains in the distance touched off a chill, as the sun that had earlier dispatched the fog was now lower in the sky would not be able to provide warmth for long on this treeless island.

In the short time before dark as we hastened our advance to our objective: we were to provide flank protection to the main body of forces moving up Massacre Valley. Advancing over this tundra was slow and tiring as the deep growth of the spongy compressed vegetation, felt bottomless, and required lifting each leg higher than we were conditioned, every step of the way. Progress was slow. We required frequent rest stops. Proceeding toward our objective was fearful as we were now separated from the main body and didn’t know what we would find ahead.

A short distance from the beach our scouts came upon a large tent that appeared hastily vacated. Food for several men was setting on a table, but examination of the surroundings did not provide any sign of the occupants. This was our first indication of life that we found this first day. Leaving this scene we traveled until near dark, when we re ordered to stop for the night. Fatigue had drained the remaining energy not already consumed by nervous exhaustion.

Digging a foxhole was no easy matter. We carried only one digging implement and it was not designed to pierce the thick ground cover. Each man was having a difficult time with apprehension and fear in this dark and unfamiliar place. There was to be no sleep as we waited for something to happen. What a great relief when the night ended, and we had not been attacked by the unrevealed enemy. The delayed landing had restricted yesterdays advance, we were anxious to move on and as we perform better in daylight.

|

| Massacre Bay, Attu Island. 27 July 1943 |

Early morning of the second day the sight of two approaching men halted our progress. The men identified themselves as part of a contingent of Alaskan Scouts. The scouts had made an obscured landing a few days before the main invasion force and advised us that a Japanese patrol was in the area, perhaps the occupants of the tent we discovered yesterday. Before departing the scouts explained to our leader the identity challenge usually by the Japanese when encountering suspected enemy. The challenge “Mushi-Mushi” would be given before engaging in combat.

A short while following the departure of the Alaskan Scouts, we sighted an approaching party, perhaps the Japanese patrol. Our leader shouted the challenge “Mushi-Mushi”. He received a counter sign response from the Japanese, who momentarily confused by our leaders challenge and the presence of the large number of us. The Japanese patrol leader impulsively decided that we were a hostile force and ordered his machine gunner to fire on us, to which we responded with return gunfire. The encounter was brief and deadly. It was shocking to have human targets to shoot at, but it was stimulating to be the victor in this action. We each experienced a range of emotions from this first encounter.

One day in support of the Infantry attack moving up Massacre Valley, two airplanes launched from an aircraft carrier joined in the assault. The airplanes were being used for a bombing mission of suspected enemy emplacements that artillery shellfire had failed to destroy. This single effort by naval aircraft was never repeated as both aircraft crashed into a fog-shrouded mountain. Fog, an unpredictable danger, often obscured the target, the ever-present mountains or the landing strip where the aircraft were to return after a bombing mission. The Air Force did provide support for ground troops from adjacent island, weather permitting.

In the days since arrival our platoon fortunately escaped gun shot wounds, however several men developed very painful cases of “foot immersion”. The water soaked tundra, flooded in many places by the run-off of snow supplied by the mountains that crossed the island. Many swollen creeks and streams had to be crossed, saturating our heavy leather boots that could not be dried. The men that failed to carry changes of stockings had the prerequisite for troubled feet. For those men who developed “foot immersion” the saturated skin finally yields to raw flesh and extreme pain. Healing this condition required lengthy period of hospitalization beyond this island.

|

| Jack London in dress uniform at Camp Wheeler 1943 |

COLD MOUNTAIN: Baptism under fire, attack gone wrong

In addition to the physical strain and mental stress that the battle ground exacted of each man, undoubtedly caused by fear and anger the toll that would affect the stability and reliability of some of them. One afternoon, a member of the platoon drew my attention to his agitated demeanor. He was pointing to the top of Henderson Ridge, from where he was convinced; the enemy was about to launch an attack on our platoon. Shorty Rodgers was certain that he saw figures of enemy soldiers atop Henderson Ridge, through the patchy fog and gusty wind. In his excited frame of mind, Shorty was able to persuade a few other men to join him in firing their weapons at the fog-shrouded ridge. A considerable amount of firepower was unleashed on the ridge, before cooler heads of the noncoms, who were now in charge of the platoon, were able to restore order. Whatever might have been looking down upon from the top of the long narrow crest was either chased off or had been destroyed. The mental stress on the battlefield can be as damaging as a physical wound.

Another victim of this battle was our fair-haired lieutenant. He was an early casualty, but not by enemy action. He didn’t have much stomach for this mission and checked himself into the medics. We never saw him again on this island. Warfare on the battlefield is quite different from the textbook version, certainly colder and wetter.

Our troops leading the attack up Massacre Valley moved at a very slow pace, due to strong enemy resistance. The Japanese controlled the high ground and were secure in their network of trenches. The enemy had a good view of the approaches to their positions from their observation post on Cold Mountain, and any movement across the valley was readily noticed and quickly repulsed. The force commander decided that we would serve the mission better by having my platoon destroy the Japanese observation post on Cold Mountain.

For the assault of the enemy observation post a replacement officer a 2nd lieutenant was appointed to lead us. Each day men were being detached from the platoon for either medical or psychological treatment. The platoon at this point was reduced to about 24 men, available for duty.

|

| Camp Wheeler Training Battalion |

Men were being detached for medical or psychological treatment each day. The climb up this snow-covered mountain was strenuous, put us near the summit in about four hours. We were signaled to be quiet and rest before continuing on. The dense cloud cover that had accompanied us was now being carried away by a gusty wind and the fog was breaking up into fragments improving visibility. Enemy observers discovered out presence and directed automatic weapons fire on our small force, making any movement above ground perilous.

The Japanese quickly rallied additional weapons to converge gunfire on our exposed position, in an attempt to encircle our platoon. The concentration of the enemy’s firepower impacted both flanks of the platoon as they tightened the circle that separated our forces. From their position of advantage, above us, it appeared that they could annihilate us. Our Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) could not rival the many automatic weapons the Japanese were now using. The reduced size of our platoon, our apparent lack of experience and weaponry was a poor match for determined Japanese defenders.

|

| Browning Automatic Rifle |

I was in a shallow depression in the ground that protected me from the traversing gunfire that the enemy was directing on us from both flanks. Any movement above ground would incur the immediate response of gunfire from the enemy. Corporal Diaz, was sheltered in an adjacent depression in the ground became restless and impatient with the distorted situation. The corporal was determined to retaliate for the thrashing the enemy was directing on us. He stood up in response to the challenge, but before he could fire his rifle, an alert Japanese machine gunner was able to inflict two serious wounds to the corporal. I crept over to the corporal and managed to bandage severe wounds to both hands, as he fumed with frustration, anger and dismay.

Our platoon leader decided that we were no match in this encounter and ordered the platoon to withdraw. In my effort to respond to the lieutenant’s order I vigorously attempted to raise myself from the prone position. This action caused my defective shoulder to unexpectedly give way and again my arm slipped from the socket. Only a few days before, while disembarking from the USS Harris, my left arm slipped from the socket, causing me to fall into the landing craft that delivered my platoon to this island. Now, once more, this painful injury disabled me. I was unable to reset the arm to the socket and certainly not while lying on the ground in this frantic setting. I helplessly struggled to set the arm in place. When I was called to move down, I explained what had just happened. I was fearful of the situation, conscious and troubled by the delay I was causing our withdrawal from this untenable position. Realizing the helplessness of my condition, two men who were positioned below me crept up to me and grabbed hold of my boots. They pulled me to a deeper hollow below the depression I was using, where I could safely sit up. With the assistance of my two rescuers, we were able to reset my arm into the socket.

The situation was becoming more desperate, as the weather and visibility continued to improve. Without the fog to blur their sight the Japanese had an unobstructed view of our beleaguered platoon. Our attack had been humbled and a speedy retreat was necessary to save ourselves and prevent additional casualties. In a matter of several minutes the platoons aggressive action had been outmaneuvered and now experiencing the affect of the enemy’s repellent gunfire. The swift moving action was a confrontation that we were not prepared to carry out. As we retreated enemy soldiers carrying automatic weapons fired at us as they charged us from their position on the mountaintop. The soldiers led by a shouting officer waving a saber in an attempt to frighten us, succeeded. Our BAR marksman unperturbed by the aggressive display by the Japanese was able to cut short their reckless performance.

|

| Map showing Massacre Bay |

It was time to depart. Leaving this position would be easier than our arrival only a short time ago. The rain suits, we wore proved to be useful for our hurried departure. The synthetic fabric of the suit pants melded readily with the snow cover of the mountainside. With gravity providing the impetus, caused our slide down the mountain to be quick and smooth. I slid down the mountain with the wounded corporal. Cold Mountain remained in enemy hands, but not for long.

It was a slow hike to the beach in order to accommodate the wounded platoon members, where the medics had established an aide station. The walk gave us time to consider how fortunate we had been to withdraw from the mountain without a fatality. Our baptism under fire would not be forgotten soon and there was disappointment of our failure to overcome the enemy. The need to withdraw was not the bold action we had foreseen, but it was a prudent choice, decided by our leader.

Better preparation for future encounters might prevent another regrettable event. The wounded men I accompanied were given medical treatment. The seriously wounded men were removed from the island, shipped to hospitals where advanced treatment was available. I asked the medical officer if there was treatment he could prescribe for me. The officer explained there is no remedy for this recurring condition, explaining that I should carefully continue to function as ably as my limitation would permit. The ligaments that secure the arm to the socket had been severely stretched and won’t be restored if I continue to strain this band of tissue.

I was next assigned to battalion headquarters for the purpose of learning communication procedures, including semaphore code as applied to flags and flashing lights. Radio communication was poor and never reliable. It was necessary to use messengers traveling on foot often over great distance and difficult terrain to maintain contact between headquarters. The highly proclaimed walkie-talkie radios were notorious failures. This radio would operate within line of sight provided the instrument was kept dry and satisfy its need for a continuous supply of replacement batteries.

It might be useful to explain why we did not use vehicles to travel between headquarters; there were no roads. It was a long while before engineers carved a road out of this forsaken wilderness. In the meantime the only vehicles able to travel over this trackless expanse were fully tracked caterpillar tractors. The trailers used for carrying supplies were fully tracked and were pulled by the tractors. When an incline, in this tundra, had to be climbed, it required positioning one tractor at the top of the rise and using a winch cable connected to the tractor pulling the trailer to reach the top. This concerted effort was required at each rise in the terrain. Moving supplies was a test of ingenuity and very hard work.

BANZAI: Terror in the night, the enemy’s mass attack

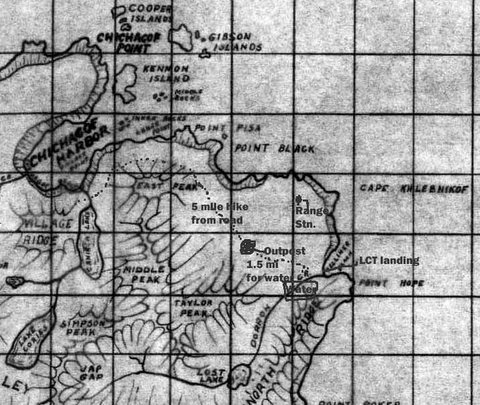

A successful end of this invasion seemed within grasp after American troops forced the Japanese from their fortified defensive positions. Americans eagerly secured the high ground in pursuit of the enemy failing at time to maintain contact and communication with adjacent American units thinly spread across the valley below.

On the night of May 29, a large number of the enemy discovered a lightly defended American position in the valley floor. In a desperate effort, using their remaining troops about 1000, the Japanese swiftly overpowered the defenders. Failure by American defenders to maintain contact with adjacent units and to provide the necessary level of vigilance contributed to the disaster. The attack by the Japanese was not carried out with stealth, creating confusion as they shouted English and Japanese expressions as they raced through the breach they had created. American defenders had difficulty determining who was who in this predawn darkness. The attack led to knife and bayonet struggles between opponent when it was too close to use other weapons. Leadership was missing as command posts were overrun in this swift turn of events. The Japanese attackers were rushing on a mission of destruction, using all of their functionally able men to kill or be killed. Surrender was unthinkable.

|

| 1944 Map showing Chichagof Harbor |

American forces advanced on Chichagof Harbor where this battle could have ended would now be delayed, as the Japanese were leading the attack, as their plan was to destroy whatever lay before them. The Japanese soldiers’ loyalty to their emperor and fulfilling their concept of honor made surrender not an option. BANZAI, this reckless attack, was the order of the day (night).

Earlier this night, I was feeling especially secure, sleeping within the perimeter of Third Battalion Headquarters. A companion and I chose to put together a pup tent, assembled from shelter halves that we each carried. We were unaware that this precisely the target of the enemy’s attack. For the first time in while, I decided to remove my boots, hoping for sound sleep. Most nights were not as quiet as this night. About 4 o’clock in the morning, the quiet was suddenly transformed by the voices of shouting men and small arms fire spreading confusion in our midst. It was difficult to locate the source of the disturbance, as voices seemed to come from all directions. I realized that the Japanese, who were shouting in English and Japanese, had surrounded us. I later learned that some of the enemy was carrying bayonets attached to stakes, using this modified weapon to stab sleeping men or anyone in their path. The enemy had assembled able-bodied men along with crippled and wounded soldiers from their hospital. If the injured enemy was unable to carry a rifle he was supplied with a bayonet attached to a stake. The rallied and inspired Japanese had penetrated our security and was creating havoc and death. While the enemy was racing about, it was difficult deciding where to go to defend ourselves. It became obvious to me that all who remained in this place of confusion were vulnerable.

Having mistakenly removed my heavy boots that night, I had to hastily get my feet back into the boots not taking time to tie the laces, grabbed my rifle, which had taken place of a missing tent pole and secured my ammunition around my waist. I decided to run toward Engineer Hill, which was about a mile behind my position. I remembered that the engineers had been constructing a winding road on this hill to provide easier access over it.

|

| Japanese solder with bayonet mounted on rifle |

As I ran toward the hill, in this early morning darkness, my boots not fully laced, I discovered that I was not alone, as other men were trailing not far behind me. In this state of confusion I was not certain which army the pursuers were serving. My race across the tundra in search of refuge and an organization able to restore order and take control of the chaos that had erupted. I was fortunate to find the road, in the dim light, that engineers had just carved across the hillside. I ran up the road until I reached the first turn where a bulldozer was parked. Voices of Americans defending the hill shouted out challenging me to identify myself. Recognition was swift and I was directed by the defenders to join them in safeguarding the position. Throughout the early morning darkness other men arrived from other positions that had been overrun. Unfortunately the Japanese found the way to this hill too. The enemy made many attempts throughout the night and early morning to take possession of the hill. The enemy failed to force us to give up the position. Our defense was sufficient to stop their advance. The enemy’s continuing reckless attacks of this hill provided American defenders unlimited targets. The Japanese attacked without exercising any caution or care. In the early light of day, surviving enemy marauders paraded across the valley floor, waving the rising sun flag, to mock and tempt us into making an ill-advised chase.

In the full light of day a grisly sight unveiled. Japanese soldiers not slain in the pre dawn struggle chose to end their lives in suicide. The vast expanse below engineer hill was a field of unsightly death. The bodies of the dead were made more horrifying by the indecent and ghastly sight of the many suicides. I was glad to leave this area.

The Banzai attack, the nightmare of terror did suddenly end the enemies organized resistance. The American landing force suffered 3289 casualties in the battle, 549 killed, wounded 1148, severe cold injuries 1200, disease including exposure 614, self inflicted wounds, psychiatric breakdown, drowning and accidents 318. Only one third of “I” company was available for duty, to establish outposts in Sarana Valley, to capture Japanese stragglers.

|

| "K" rations - breakfast, supper and dinner |

A field kitchen was delivered with the baker and cooks restored to duty and provide the company with hot meals. All of the company were eager to give up the monotonous “K” ration which had been our only food for weeks. We learned soon of the many ways Spam could be prepared. It was served fried, baked, sautéed but never with any fresh food. Other food products were from a can or reconstituted from a dry mass or powder. Flour was supplied could be used to bake bread except for the one missing ingredient, yeast. I volunteered to hike to the beach area to procure the yeast from the quartermaster.

The hike to the beach required climbing Gilbert Ridge and would take a day to complete. On my way I discovered increasing evidence of civilization as my hike reduced the distance to the beach. A new road servicing many trucks and jeeps traveling with complete indifference as though this artery had always been in place. It was an unexpected wonder to me. The area was totally unrecognizable, as I had last seen this place as an invader.

When I returned to the company with the yeast, I was greeted with cheers, my service was appreciated. The company baker had been preparing for days to bake bread. He had been collecting emptied Spam loaf cans to use as bread pans. The day following my hike to the beach, we were served a ration of bread, which was the most wonderful part of the meal. Hungry men would make forays at night to the kitchen tent and carry away bread meant for the next day’s meals. The Captain was quite disturbed, if he missed his share of bread. To solve the problem, he assigned a guard to the “bread outpost”, a simple solution to a vexing problem.

It was peaceful in beautiful Sarana Valley, until the Williwa arrived in early June. The Williwa is a wind and rainstorm with steady wind of 100-mph velocity, an added misery hurled at the surviving troops. The Company was bivouacked in large canvas tents that sheltered eight men. The tents required continuous attention during the storm to prevent the tents from collapsing. Failure to adjust the tie ropes, to accommodate the shrinking canvas, could either snap the tent pole or tear the canvas, which either case could cause the tent to crash. Half of the tents sheltering our Company did collapse. The storm lasted three days, but it seemed longer, especially when it was necessary to use the outdoor latrine in gale force winds.

When we had to leave the otherwise calm and beauty of Sarana Valley, our Company boarded the troop ship Tjisidana, for a short voyage to Adak, another island in the Aleutian chain. At Adak, much to my surprise, I found a remarkably developed settlement. Adak was the forward base for military operations in the Aleutians with many roads and Quonset huts in place. After our arrival we were issued new clothing, foot gear and equipment to replace whatever was worn or damaged. Our ranks were filled with eager replacements, who were also fearful of the adventure that lay ahead. Before we left, there was time to play baseball, attend a movie theater and remember how to relax. An ally was to join in the invasion of “Kiska”, this was to be a joint operation between Canadian and American troops.

On boarding the Tjisidana, the troop ship that would transport my battalion for the short trip to “Kiska”, the Army chose as the irrational occasion to pay the troops. It was untimely as there was nothing to purchase, but it was perfect timing for dice and card games we used to fill the idle time before disembarking. There was little space for all the games that did pop up, so the shower stalls were pressed into use as dice parlors. Money changed hands quickly. Fortunes of that time were won and lost during the course of that short trip.

In an effort to improve conditions during hostilities, each man was issued 24 cans of Sterno, to be used in warming the new “C” ration. Curious men soon discovered that the alcohol in Sterno could be separated from the other ingredient in the can, and swallowed to cause a drunken stupor. Without delay the Sterno was collected and was never seen again. Warming of the canned ration would have to be heated in another manner. In the meanwhile, the ship would provide the hot food while we were onboard. There was however, no place to shower.

|

| Troops landing at Kiska |

Our landing site on “Kiska was a narrow beach that ended at the base of a promontory at least 60 feet high. The corridor from the ocean to the beach was lined with huge boulders and rock that landing craft bringing the troops to shore had to negotiate. The narrow passage permitted only a single boat to reach the beach before the next boat was able to enter the maze. The leading boat had to return to open sea, after discharging troop passengers, traveling in reverse, as there was no space to turn about. Off loading our landing group required time than planned. Our arrival and landing was accomplished without enemy resistance. The only sounds to be heard were the roar of arriving and departing landing boats.

After scaling the cliff, we set about cautiously in search of the enemy. Before dark on this first day, August l5, 1943, our advance was halted and we were ordered to dig in. Throughout the night sporadic rifle fire pierced the quiet vigil as we awaited the charging enemy. The sound of rifle fire would occasionally become intense, leading us to believe that the enemy had been located. In the presence of daylight, we were unable to find any evidence of a skirmish in our sector, however another unit entrenched nearby had sustained casualties during the night. This Ranger unit had the misfortune of shooting at each other in the dark. A rifle fired by a jittery soldier into the darkness resulted in a retaliatory response that staggered out of control. The enemy may have departed this sector, but he left a deadly reminder.

On the second day we continued our advance, anticipating the emergence of the enemy. By the end of the day, reports were received from other sectors confirmed that the Japanese had evacuated “Kiska”. 35,000 combat troops had been assembled for this mission but the enemy had managed to slip away in this fog shrouded setting. Despite this merciful climax, 313 men became casualties, 24 men shot to death by their comrades in a similar fog that covered the Japanese withdrawal. We left “Kiska” before the end of August, once more climbing aboard the troop ship Tjisidana for another voyage to wherever destiny directed. The Bering Sea, turbulent and enraged, pounded by a cold and dispassionate wind; summer in this part of the world had ended.

The ship was now our refuge and shelter from weather conditions that tormented the island. The crowded conditions and complete lack of privacy aboard the Tjisdana, was an endurable exchange for warmth and security of the ship. There was little to regret leaving the Aleutian Islands. Before long we were sailing in the Pacific Ocean, which is noticeably calmer. We sailed into the wake of a developing storm one-day and the seas became rougher and more violent with each of the three days of the storms term. At the height of the turbulence, the rampaging sea produced waves that stretched 35 feet above the ship’s deck. Passengers were not allowed on deck, a view of the ocean was possible from the passage opening to troop quarters. The only safe place for passengers was our bunks. While lying in this narrow berth, it was necessary to hold onto the steel bunk frame. It wasn’t possible to sleep during this period as the ship plunged, rising and falling in the rough water.

Only a small number of passengers chose to eat in the cafeteria during the storm. The initial meal when the storm commenced was a calamity. The mess compartment became a scene of disaster, with waste cans upsetting and spilling the wet contents on the deck. The dining benches slid across the slippery floor becoming missiles driven by the force of the pitching ship and colliding with anything in its path. Other unfastened fixtures slid across the floor at breath taking speed. Many injuries resulted; arms and legs were broken in this accident inclined condition.

During the height of the storm the ships stern was out of the water when the crest of a wave lifted the vessel. The screw or propeller that drives the ship should not be out of the water. If this occurs, the propeller without resistance of seawater, spins ungoverned vibrating wildly shaking the entire ship. This trembling caused much concern among the passengers. After a while the ship’s crew stopped powering the vessel, preferring to steer the ship into the waves until the sea became calm. The convoy of ships that we accompanied on this journey had scattered and we were alone on our route south to Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands. Welcome to Waikiki.

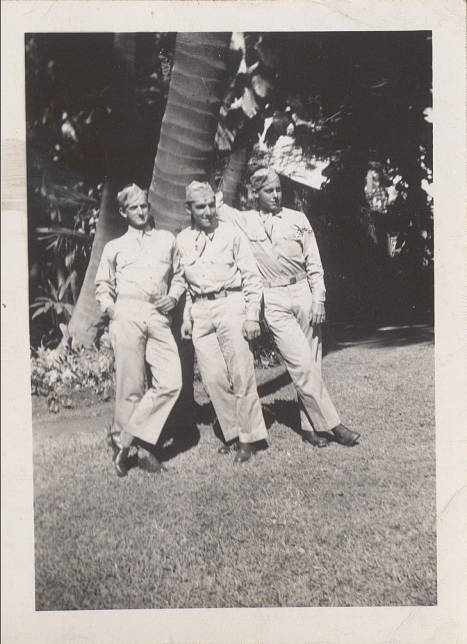

|

| Jack London (center) at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Waikiki |

21 months after the attack on Pearl Harbor restrictive measures were still being practiced on the island. It was as though the inhabitants were under siege. A curfew was being enforced doing away with nighttime activity. Window shades were drawn at night, the city of Honolulu retired at 8:00pm. Pillboxes, concrete gun emplacements, were still in place on most beaches. The bars served a synthetic whiskey, as popular brands had become a hostage to a black market. Even with all of the restrictions, Honolulu was a great town to visit on your day off.

My regiment was lodged in a recently vacated prison camp. The previous occupants were American residents of the islands of Japanese ancestry, who had become (spy) suspects in the panic that followed the attack on Pearl Harbor. Now my regiment became the tenant of the buildings and grounds that was to be our base for a brief period. At least for now we had a roof over our head, and we would sleep above the ground. The camp was located in the hills of the rain country above the village of Waihawa. Honolulu is less than an hour away by speeding bus. Liberty passes were available permitting visits to the world- renowned attractions, Honolulu and Waikiki. This island was a great place to recover from the depressing events we left behind in the Aleutians.

BURTON ISLAND: Friendly Fire, turned hostile

A strenuous training period began in September 1943 with an extensive buildup of men, many new faces to fill openings in the ranks. New equipment was demonstrated and issued emphasizing amphibious assault landings. Field maneuvers were employed to exercise the skills to operate the new equipment and learning how to execute with other support services that provided war tanks, flame thrower and bazookas. With this additional power and training we once again boarded a troop transport for the assault on the Japanese occupied Kwajalein Atoll on January 29, 1944.

|

| Namur, Kwajalein Atoll. 2 Feb, 1944 |

The Kwajalein Atoll assault required that my company execute landings on several small islands. Some islands were only 400-500 yards wide and 2 –5 miles long, elevation about 17 feet. The battle was very destructive, as the naval battleship group supporting the attack, prepared an intense concentration of artillery gunfire on very small islands. Kwajalein Island was reduced to rubble, not a tree was left standing, all of the buildings and enemy emplacements were demolished. It was difficult to walk in any direction; vehicles had difficulty maneuvering on any course. Despite all this devastation, some of the enemy managed to survive.

My company was ordered to relieve another company that was engaging the enemy on Burton Island (code name). We were delivered to the island just before night of the 3rd day of the whirlwind battle. We were ordered to dig in for the night, as we would relieve the attacking company in the morning. I was preparing to settle down near the position my platoon leader designated as our command post (CP). Though the battle action was about 200 yards away, there was no shelter above ground that would shield this rear position. Artillery shellfire had leveled the ground of all vegetation. There was nothing to block gunfire that was continuously cracking about us.

Even in the midst of a tumultuous setting the company was able to cope with the threatening conditions. The situation changed when an exploding artillery shell landed about 75 yards from our command post. Moments later another shell exploded about 75 yards on the opposite side of the command post. The Japanese no longer possessed artillery guns capable of producing a blast and concussion of that size. It suddenly became apparent to the lieutenant and I that a misguided artillery explosion would probably land in our midst.

The simultaneous action of the Lieutenant and myself as we reached for the radio to call our headquarters to silence the artillery piece firing at us. Unfortunately our call to headquarters was not in time to silence the offending gun. We failed to stop the last shell that exploded where several men had prepared a position in the ground that would safeguard them through the night. There is no protection for an artillery shell that lands in your emplacement. The deaths of the men had a demoralizing affect on the company. The misdirected artillery did irreparable harm. Incidents like this would occur again in the days that followed. My platoon was relieved of further action on this island. The shock of losing the platoon members and the lack of confidence in support artillery left us incapable of further military action.

|

| battle of Kwajalein, February 1944 |

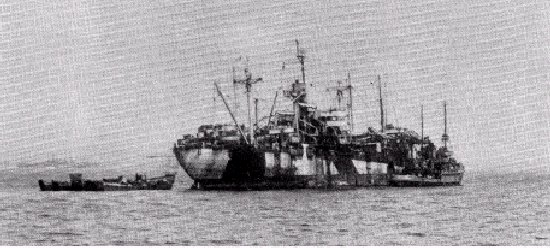

The time to leave Kwajalein Atoll was advanced for my infantry company. We boarded a Naval Cargo (KA) vessel that was to return us to Oahu. We were the only passengers on this large ship that had just unloaded its military cargo. There was abundant space in which to stretch out, unlike other voyages. Before the ship was to leave Kwajalein, it was to transfer fuel to another vessel in this location. The destroyer to receive the fuel approached our (host) vessel too swiftly and caused a collision. The bow of the destroyer sliced a gaping hole to the hull of our host ship just above the water line. The frustrating accident occurred as preparation was being made for the ship to get underway, transporting us from the battle zone. After the fuel exchange the ship’s crew set about to repair the damage and make the ship seaworthy for the trip to Hawaii. Scaffolds were placed over the ship’s side for welders to repair the damage and seal the hole in the hull. The work continued into the night with the use of work lights. Throughout the night, Japanese bombers were passing over these embattled islands seeking targets of opportunity.

Whenever the ship’s radar detected the approach of enemy planes, lights were extinguished and welders were recovered from the scaffolds. Before daylight repair of the torn hull was complete and the ship was prepared to sail.

Preparation to get underway was again interrupted for another task. Our ship was brought into position to tow a disabled destroyer to Pearl Harbor. The destroyer had damaged its propeller and rudder, while attempting to negotiate an opening between two islands of the Atoll. Soon after the cable connecting the two vessels was secure the ship departed the ravaged islands. The trip was slow paced as the ship had the burden of the tow. One day during the voyage our progress stopped when the towline connecting the two ships separated. It required Herculean effort to reconnect the towline. It was urgent to be underway as we were motionless in water that Japanese submarines patrolled. Diamond Head was a welcome sight before heading into Pearl Harbor an end to this mission.

|

The voyage to Oahu afforded time required to heal collateral wounds, consistent with the psychological trauma experienced by some members of my platoon. Many men were scarred by the horrifying accident of the artillery explosion. The expression most often heard, “they didn’t deserve to die that way”, was repeated many times. We had expected better. What we encountered was confusion and disappointment, by failure in the ranks.

Friendships severed by the bungled artillery episode and other horrific incidents demonstrated the fragility of the fraternity that bonds men. Replacement riflemen assigned to this command would find calm indifference greeting them at their new assignment. We were recovering survivors soon to be prepared for another assault.

Shortly after returning from Kwajalein, I was summoned to the regimental personnel office. I was interviewed by the personnel officer and his adjutant for the position of file clerk for this office. One of the benefits of the position, I would be relieved of further duty with my rifle company. The offer of the position and my acceptance did not require any additional negotiation. I was soon working with a team of specialized clerks and fortunate to receive this reassignment. My attendance at junior college and a Chicago Business College was the reason for my selection to the personnel office. I worked among Company Clerks who prepared entries in Service Records of each man in the Regiment. Records were compiled of every event, inoculation, combat mission, commendation, disciplinary action or injury in every man’s experience.

|

| Sinclair Oil, Waukesha, Wisconsin, 1938 |

Working in the Personnel Office I soon learned of the background and duties other associate clerks performed. Sergeant John Gorog from Waukesha, Wisconsin was usually found with a cigar gripped between his lips, filling the air with a thick pungent trail of smoke following him. Sergeant Gorog was the noncommissioned officer (leader) providing guidance, liaison and cheer between clerks who need support. The good Sergeant knew his staff well and would appear whenever his help was needed. He expressed a longing to return home to his position at J.C. Penney, where he had been assistant manager.

At a desk adjoining mine was the clerk who attended to the personnel affairs of all commissioned officers of the regiment. Warren Hoeft was the most the most disciplined individual I had ever met. The discretion he practiced made him an excellent choice for this position. If rumor of an officer’s indiscretion were being discussed, confirmation would not be affirmed or denied by Warren. He served this position well, never supporting any gossip.

The Morning Report Clerk had to deal with considerable detail as the composition of manpower changed daily. The function of this position was to supply an accurate count of men available for duty, as the number of men relieved of duty, and for what cause. All of the numbers had to be balanced each day. Filling this position was Sam Trubowitz, a gentle, patient understanding individual. The manpower count was submitted each day, by First Sergeants of each company in the regiment to the desk of Sergeant Trubowitz. The information had to be carefully examined as the First Sergeants had not been chosen their positions based on their mathematical skills. On many mornings there would be a line of Sergeants requiring Sam’s assistance to balance their report. The good humor and endless patience of this skilled clerk deserved admiration.

The Courts Marshall clerk, Carmen Iaccubucci, tended to another busy desk. Carmen was a law student until Selective Service (the draft) interrupted his education. Carmen’s school had prepared him for the constant flow of work processing the illegal documents required in court’s martial. It was bewildering trying to understand how men living in conditions of great restraint and discipline had the will to violate the law, offend authority or in some manner become an outcast. Perhaps a view of the helplessness or hopelessness in this tragedy created a demon they chose to embrace.

In the summer 1944, I began a three-day pass in Waikiki. On the sidewalk in front of the Moana Hotel, I noticed a familiar face of a soldier passing by. It was a most unlikely setting for two men from Chicago to meet. Alvin Stahl, a Lieutenant in the Air Transport Command had just arrived at Hickham Field and was scheduled to stay three days. On his insistence, Alvin had me check out of the hotel I had just rented. I moved to the apartment that Alvin and the other members of his crew were occupying at Hickham Field. For three memorable days these men, officers in the Air Force, wined and dined with me, including giving me my first flying experience. It was a good time with great company and none of this had been planned.

On another day later that summer, I received a phone call from another friend in the Air Force, who was passing through Hickhkam Field. I explained, in our phone conversation, where I was stationed and how to find me. In a short while Arthur Marcus, a friend from Chicago arrived at my office. Once again I was pleased that a friend was able to visit, together we were happy to refresh our friendship in this place, so distant from our homes.

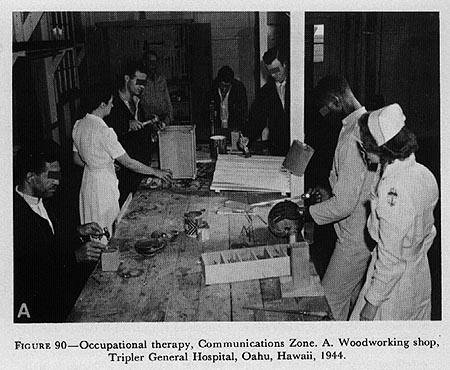

|

| MacArthur, Roosevelt and Nimitz on USS Baltimore 26 July 1944 in Pearl Harbor |

Troop training was being vigorously practiced new field techniques and assault weapons were introduced, that was only interrupted by a visit of the Commander in Chief. He was here to meet with General Douglas MacArthur. The Seventh Infantry Division was assembled and reviewed by President Franklin Roosevelt. The President viewed the division from an open touring car. It was only as we paraded that we recognized the importance of the person that had brought us together in our neatly pressed uniforms. Many changes in command positions followed the President’s review. A short time later troop transports were being and wee accompanied by rumor and speculation. Most of the Seventh Division boarded troop transports bound for an undisclosed destination, leaving Pearl Harbor September 15, 1944.

The Division was aboard troop ships for more than a month before the October 20 assault landing on Leyte, one of the Philippine Islands. We learned later that plans changed as the convoy carrying the Division sailed west. The planners must have had difficulty coming to an agreement where our Division would be more effectively employed. The event, liberating the Philippine Islands, promised by the revered General MacArthur, who often repeated his declaration, “I Shall Return”. The battle on this jungle island lasted until January 1945. Numerous casualties and many lives were counted, recovering this island from the Japanese. The battle reflected the strong character and resolve of the United States and preserved the pledge made by the General.

I did not leave Oahu with the Regiment. Our office group and other administrative personnel of the division, were to be dispatched to arrive after a bridgehead had been established. Our function was to safeguard Division records and establish a headquarters at the destination. We were unaware of where we were being taken or when we were to arrive. Our embarkation of the troop ship launched a voyage that lasted 82 days. The sailing was punctuated by long layovers in the harbor of Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands and the harbor at Pelilu in the Palau Islands. The Navy’s plan to position this ship and many other vessels in safe harbors while naval battles of the Philippine Sea were in progress.

It was January 1945, when we disembarked near Tarragona on the island of Leyte. During the long voyage we were unable to communicate with families of friends, a period that caused anguish and needless fear. Mail had been accumulating for weeks, was finally delivered. Damaged Christmas gifts, food items reduced to crumbs and mold were salvaged from sacks of mail piled and crushed. Some of us learned of births and deaths that occurred weeks before. It was a good feeling leaving the ship and to walk on solid ground. The battle for this jungle island was now over and the work of the personnel office could resume.

| Leyte, 1945 |

Incidents took place during the course of the voyage that were of interest and humorous. For many weeks I read books borrowed from the ships library, stopping only when necessary. There was a period when I was drafted into playing Bridge; the game commenced after breakfast each day continuing until dark. Such marathon episodes filled the hot days of these equatorial waters. This ship, an Army Transport, could supply only seawater for showers. This very hard water used with the soap provided produced a scum on the skin that was difficult to remove. One day, while the ship was anchored in the harbor at Pelilu, we sighted an approaching dark rain producing cloud that would soon pass over the ship. Many of us left the deck for our quarters to remove our clothes, hurriedly returning to the ships deck with a bar of soap and await the arrival of the rain. The rain water shower was a tonic. I passed Sam Trubowitz on my way to my bunk to dry myself. I told Sam of the rainsquall that was passing over the ship. Sam decided that he wanted to take advantage of this opportunity for a fresh water shower, and began removing his uniform. Sam found the rain still showering the ship so he quickly produced a thick lather and enjoying the pleasure of the foam was a joy about to end. The cloud that provided the rain had moved on all too soon. My good friend was left with abundance of suds and without the soft rainwater to wash away the lather. I believe that Sam had to be the most hairy human I had ever seen, he might have rivaled a bear. The soapsuds he had created had tangled his body hair. There was little else to do, but retreat to the ships shower and hope for the best.

A large new office building was erected by Philippine natives for our Personnel Office. It was spacious work place, providing us shelter from frequent rains. Electricity was provided courtesy of another agency that failed to guard their generator. Because of our long delayed arrival there was much work required to catch-up. Almost three months of active combat conditions produced numerous changes. Many reports of men injured and evacuated as well as replacements were received. All of these changes had to be recorded and we were the record keepers.

In honor of Passover 1945, Jewish soldiers were invited to a holiday celebration at the headquarters of the Fifth Air Force. The well-lighted operations center, provided with highly advanced office equipment was located in a jungle, well hidden from sight of passing enemy aircraft. The festivity was well attended, as it featured the appearance of the Lind Brothers; three Cantors, who would normally serve pulpits in Chicago Synagogues. The memory of that event still pleases me, as it allowed me to renew faith with many other men in this part of the world, so far from home.

The recovery period for damage experienced in Leyte was a short respite as the Regiment was filling openings in the ranks with replacements. We were again chosen for a continued advance on the Japanese Home Islands. Equipment was being prepared once more and loading was underway, for an attack of another island, Okinawa. When the name of the island was disclosed, it drew a blank response. Little was known of the island, as not much current intelligence was available. Few Americans had visited the island. For many years the Japanese had declared this island off limits. Visitors were not welcome, as they were creating a fortress. The slight amount of information collected proved to be inaccurate. The island was a Pandora’s Box waiting to be opened.

In an effort to improve the mission of our office, I offered a suggestion to my Captain, whereby I would depart and travel with the Regimental Headquarters group. I would then be available to receive and catalog transfer records of the wounded, in a shorter time than was possible after the battle of Leyte. The Captain agreed with the proposal and was pleased that I was willing to risk landing soon after the assault troops. I would travel with the forward echelon, and land with the Regimental Headquarters team. I traveled aboard a Naval Transport, APA 92, named the USS Alpine, the name would be etched in my memory for an event soon to take place.

|

| USS Alpine APA92 |

EASTER SUNDAY: A Kamikaze welcome to Okinawa

April 1, 1945 Easter Sunday April Fool’s Day, was also Landing Day on Okinawa. It was a bright sunny day, the sea was calm, well suited for the invasion about to be launched. An invasion fleet consisting of 1500 surface vessels and four infantry divisions had been assembled for this land assault. The atmosphere was apprehensive, men of the early landing group were tense as they left the ship, boarding landing craft that carried them swiftly out of sight. They were being delivered to a beach and an unknown destiny. Those of us remaining aboard the USS Alpine wee to wait for the beachhead to be established before disembarking. We seemed invulnerable and secure on the ship in the presence of this armada consisting of many warships including an umbrella of carrier launched aircraft.

Late in the morning, two disabled landing boats were towed to the port side of the USS Alpine. Each boat had encountered air-bursts fired by Japanese artillery causing many casualties. These men had left the ship earlier and were being ferried ashore, when they came under attack. The mood aboard had been cheerful, prompted by early reports of success at the beach, suddenly changed to disappointment, as we watched the dead and wounded men being removed from the boats.

Our landing force moved inland swiftly, as the enemy decided to let our troops ashore with little opposition. Our opponents chose to contest us at other sites, when and where they preferred. Throughout this invasion day, the ship’s crew continued unloading supplies from the starboard side of the ship onto shore bound boats. From the port side of the ship, the crew tended to casualties being returned from the beach. It was critical to unload as much cargo possible and to leave this position close to the island for a safer nighttime location further out at sea. The ship would return in the morning to continue unloading cargo. The time for departure was delayed. About 7:00PM the ship began moving out of the bay toward the open sea. Our departure was also the time that the naval aircraft defending this operation retired to the aircraft carriers at sea.

As the USS Alpine began moving from the anchored position, my attention was attracted to the dull pounding sound of anti-aircraft guns firing in the distance. I saw a continuous stream of orange tracers streaking across the distant sky. The tracers I was watching were attracted to a target too distant for me to identify. However this focused anti aircraft gunfire was rapidly moving toward the position of the Alpine. The vast amount of tracers racing across the sky gave an appearance of a cosmic display. I was unable to find the target in the sky that had every ship’s gunner’s attention. Then a sudden glance allowed me to see four low flying airplanes. Approaching swiftly, they flew at an altitude so low that they were only visible for brief glimpse. I was able to recognize the Japanese Rising Sun on the wings of the airplanes.

I watched this unscripted scene develop as a casual observer with no more alarm than I would have experienced in a theater watching a movie. But the action was approaching our vessel. What had been calm restrained, was now a scene of impending violence. From my position on the deck, close to the bow, I tried to track the rapidly moving targets as they had shortened the distance to our ship’s position. The Japanese airplanes were traveling a course perpendicular to the direction the ship was moving. For a few moments I wanted to believe that the ship was in no serious danger, hoping the airplanes would cross our path and not be a threat.

|

| A Ki-43 III-Ko, piloted by 2nd Lt Toshio Anazawa and carrying a 250 kg bomb, sets off from a Japanese airfield for the Okinawa area, on a kamikaze mission, 12 April 1945. School girls wave goodbye in the foreground. |

Suddenly the airplane closest to our path managed a sudden right turn, putting it into a dive aimed at the USS Alpine. I watched this abrupt change in direction in astonishment. I was then convinced that the ship was about to be strafed by machine gunfire. I was unable to watch the airplane complete the dive as my view was blocked by the ship’s superstructure.

To protect myself, I flattened my body against the ship’s forecastle, at the same time, adjusting my life belt. When I next caught sight of the plunging airplane, it was a moment before it cleared the ships superstructure. I watched in horror as the plane broke through #3 hold, exploding in a massive roar, accompanied by a huge ball of fire. The sight and sound of the catastrophe stunned everyone witnessing the blast.

Watching this situation develop, I had the strangest feeling that this was a violent scene from a movie, but the noise of the crash and the brilliance of the flame quickly returned me to reality. Other witnesses to the explosion, like me, were awe stricken, seized by disbelief, and waiting for someone to lead us from this disaster. For what did not seem possible, did happen. It was after a long anxious delay that the ships speakers blared instructions to the ships crew and admonished the troop passengers, dispelling any cause to panic.

The crew’s response to instructions was swift. Crewmembers assigned to fire control reported to their stations and began attaching hoses to hydrants. Fire fighters received a severe shock when they discovered that no water would flow from the hydrants. Apparently the explosion had destroyed the water pipe connected to the hydrants. Emergency pumps were quickly put in service and ocean water was siphoned to pour over the fire. The flames burned seemingly unaffected by the water.

Notwithstanding the enormity of the fireball and the intense heat it produced, I became aware of collateral damage to the ship. My attention was attracted to an assembly of small boats facing the starboard side of the USS Alpine. Crews of the small boats were using their hoses to pour water on the fire through the huge hole torn in the hull, produced by the force of the explosion. Subduing the fire was not going to happen soon, as the fire burned most of that night. The vast amount of water poured over the flame had a noticeable affect on the ship’s stability. The ship was beginning to list markedly.

Other small boats equipped with smoke generators were employed to cloak the Alpine in a dense smoke shielding the ship from marauding enemy aircraft expected during the night. By early Monday morning the ships fire fighting crew finally extinguished the fire, even as another drama was about to unfold.

The dense smoke shrouding the ship limited visibility on deck. In this dense vapor there was a muffled stillness that earlier was swarming with men with voices shouting, yelling and crying in dismay. This was to be the stage for another unplanned incident. In this unnatural atmosphere and subsiding calm another vessel, perhaps as large as the Alpine, penetrated the smoke and struck the Ship a glancing blow as the two ships bumped.

Sight of the offending vessel perforating the smoke causing this phantom like appearance was difficult to understand would this mysterious ships intrusion result in further danger to the Alpine? The collision was gentle but of sufficient impact to tear a large floatation device from its mounted position. The damage might have been considered minimal, but watching the incident develop added anxiety to a day and night already filled with dread.

There were no additional air raids that night to threaten the ship as the crew managed to sail the Alpine out of view of the island. A welcome sight was the daylight, after an evening and night of terror and helplessness. The Kamikaze (Divine Wind) had delivered crippling damage and injury to the USS Alpine that Easter Sunday killing 21 troop passengers, wounding 26 crew and passengers.

A large repair ship arrived at the side of the Alpine early the morning following the Kamikaze attack, to repair the damaged hull. Sailors using torches began cutting away the torn metal from the ruptured hull. The repair vessel supplied with steel plates was prepared to seal the opening and make the ship seaworthy. Following the temporary repair work at Okinawa the ship returned to the United States for permanent restoration.

On April 2, we were informed that the beachhead was now secure, our headquarters group was anxious to be put ashore. We brought ashore the personnel records leaving the vessel for an unexplored destination.

|

| USS Alpine 3 April 1945, under repairs |

The battle for Okinawa lasted 81 days. The Japanese defenders on the southern end of the awaited the approaching American Infantry resolute in their determination to inflict the greatest number of casualties possible. The enemy’s, long presence on the island, benefited their knowledge of distances between significant landmarks made their established large field guns very effective and deadly. Many Japanese cannons were placed in caves with only the gun barrel protruding. The modified cave opening, sheltering the enemy’s artillery hindered American artillery’s ability to destroy enemy guns being fired from these offending positions. The grounds approaching the cave openings were scenes of utter devastation. American mortar, artillery and bombs failed many attempts to eliminate Japanese artillery. Hundreds of pits and craters surrounding many caves were the results of difficulty of repeated attempts to silence the hostile guns.

American anti aircraft artillery challenged the nightly visits of Japanese bombers. Generally the anti aircraft response posed an uneasiness for American ground troops. There was less to fear of passing enemy bombers that were seeking suitable installations to destroy. The counter-action of our anti aircraft gunfire, attempting to drive off enemy bombers, subjected ground troops to unexpected harm. Anti aircraft ammunition that filed to explode in the air often did explode after plunging to earth and landing amidst dug-in ground troops. Friendly fire was often deadly.

On a particularly anxious day, during the battle of Okinawa, the Regiment was expecting the arrival of replacement infantrymen. I was instructed to meet and escort the replacements to our Headquarters. Before I was able to contact the group, they had come within range of Japanese artillery. Many of the replacement soldiers became casualties even before they received their unit assignment.

On another occasion, I was asked to assist a Signal Corp group connecting telephone wire between command posts. It was a simple matter, moving swiftly across a field with a spool of wire, supported by a pole passed through the core with two of us holding each end of the pole. It did not take long before an enemy artillery spotter became aware of us, as we raced across the field. The Japanese were successful in blowing up the wire, however we continued until we became breathless, and finally finding refuge in a large culvert. That was my last wire connection experience.

On a visit to the Seventh Division Pot Office, the shaking hands of a letter sorter became the focus of my attention. The man’s face reminded me of someone from boyhood. Finding a friend on this war torn island was more than I would have expected. Jerome Unger was in my Division, assigned the 32nd Infantry Regiment. His embattled unit subjected to almost a week of intense Japanese Artillery fire. His unit was unable to move in any direction until guns firing upon them had been destroyed. Jerome was a casualty of that encounter and was now temporarily assigned to the Post office for therapy. This was an unplanned meeting in an unexpected place that took ten years to happen.

|

| US Flag raised over Shuri Castle |

Several fierce engagements were inevitable before the battle of Okinawa would be resolved. It was necessary to control strategic hills and ridges in the southern end of the island, including Shuri Castle and Naha City. The Marines in their haste to capture Naha City, failed to eliminate the strong pockets of resistance, including many determined snipers, who hindered passage through the city. When our Headquarters relocated, our route through the city was hurried. The trucks transporting us raced through the streets, dodging obstacles in the road and trying to avoid sniper gunfire.

Many rain-filled days made the battlefields very muddy, causing great hardship and unavoidable delays. Troop movement was difficult. Strenuous work was required to extricate the trucks and cannons from the mud. It was a beastly time.

The Okinawans (civilians) living in the combat sector were unable to remain in their homes, currently surrounded by the battle being fought nearby. These dispossessed people kept out of sight during daylight. In the dark of night they would leave the shelter of the caves to seek food. Vegetables were growing in the unattended fields. Movement of the displaced civilians in the dark posed a serious security problem. It was impossible to recognize these noncombatants and resulted in fatal confrontations. To prevent these nighttime incidents, we were ordered to collect the civilians, removing them from the caves and trucking them to a safer area. I participated in this operation. I would crawl into a cave, speaking softly trying to assure the many faces in the dark cave, lighted by a small flame. I explained the plan for their protection, which was not simple, considering the language barrier. I would reach out to a child, coaxing it with a piece of candy, to come to me. With the child in my grip, I would leave the cave, followed by the mother of the child. The other relatives would join in the exodus. This plan was repeated many times until all of the caves were evacuated.

Before the battle for Okinawa ended, our office staff was assembled, and we resumed our function. The battle in Europe had ended, and replacement Infantrymen were now available. This combat theater would now receive whatever was needed to fulfill the mission. A policy for the early release from the Army and furlough was announced. The intention of the program was to reward soldiers fortunate to have survived the earlier battles. Based on the point system used, I qualified for a furlough, described as “Temporary Duty for Rest and Relaxation” (TDR&R). A 45-day leave of absence, commencing on my arrival at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. The response of my Captain when I presented my request for furlough, “I can’t let you go, I need you and there is no one to replace you”. Following some heated negotiation, he agreed to approve my request, if I trained a replacement. My Captain offered to classify my travel a priority and have me returned to the U.S. by air transport. I declined the convenience, explaining that my preference was to travel by ship. It was difficult convincing commanding officer that a replacement would do well filling my position. I finally learned that I was appreciated for the work I had been doing. The Captain expressed an additional compliment to me, telling of his intention to honor me with a commendation and a Bronze Star, for the work I volunteered and assumed by going with the early landing party to Okinawa. He felt my effort was important in producing a higher level of efficiency and service than was possible to render following previous combat operations.

By the end of June 1945, Japanese defenders on Okinawa ceased effective resistance. In preparation for my departure to the U.S., I began tutoring my replacement. Each day, I had a lesson plan meant to prepare this man for work I had been performing the previous 17 months. I was nervously awaiting approval by Division Headquarters of my TDR&R furloughs request and travel assignment. Before mid July, my fear of disappointment was relieved and all was approved. I felt that my replacement would be able to carry out the function of my position. I was ready for departure, but I was required to sign an agreement. I would make no effort to seek assistance to secure my release from the Army from any political officer (senator or representative) while at home.

HOMEWARD BOUND: The wake of an Atomic Bomb

Leaving Okinawa as a passenger aboard a Naval Troop Transport was unlike many similar voyages, this time I knew where I was going. I knew but a few of my travel companions. I was traveling with soldiers from many other military commands stationed on the island, assembled on this ship sailing home for furlough. Although we were in perilous water, the mood, spirit and atmosphere among the passengers was relaxed. We were going home. As there was little else to do, dice and other games filled the time between meals. Very large sums of money traded hands many times before the voyage ended. Sailors bankrolled some of the on-board casinos, usually circled by spectators watching the high stake games.

Army personnel on board being served in the ships mess was an unusual treat as it was clean dry and almost bug free. The food was more appetizing than to what soldiers were accustomed. The bread, a staple of a meal was now in abundance. However, the first meal was a disappointment. It was not what I had expected, on finding black speck, “bugs in the bread”. Looking around the room I watched earlier diners picking the dead critters from the sliced bread, which left a scant amount to eat. My initial reaction and response to this challenge, was refusing the bread being offered, though I had been contemplating this first meal with delight. At a following meal, I met the Petty Officer in charge of the mess. I expressed to him, how pleased I was with the meals he served, but disappointed in the quality of the bread. I was about to explain a solution that I felt might remedy the dilemma. Before I was able to give my explanation, he hastened to apologize for the condition of the bread; adding that the ship was unable to receive fresh flour. He then listened to my suggestion; to sift the weevil out of the flour before baking, which brought a quick reply: "the bread you are about to eat was produced from flour that had been carefully sifted".

|

Traveling through the smooth sea produced a relaxed mood among passengers that was evident as the voyage began. This restful appearance changed the day of the news announcement, heard over the ship’s speakers, telling of an “Atomic Bomb” dropped over the Japanese City of Hiroshima. An explanation of what the consequences of this explosion meant to the world was described. I do not believe any of my travel companions or I fully understood the impact of this event on our lives. Most of us were to return to Okinawa, following our furlough, to join the assault of the Japanese Home Islands.

Three days later the announcement of another “Atomic Bomb” dropped on the city of Nagasaki was listened to with greater interest. Days later, the astonishing news of the Japanese surrender absorbed every ones attention. I believed all the gamblers took the day off, when that message was reported.

I needed to consider how these fast-changing events would affect my situation. What is to happen to this shipload of casuals, now in the middle of the Pacific Ocean? The answer would soon learned.

The ship arrived in the island harbor of Guam. Before we could disembark, another ship carrying USO entertainers, led by comedian Eddie Bracken, including musicians, singers and dancers, moved along side our arriving troop ship. To every ones delight the cast came aboard our vessel and performed an impromptu program on the deck of the ship. Our arrival in this port concluded my travel aboard this vessel. All casuals were put ashore in a camp, to await further disposition. The ship that brought us to Guam had been reassigned to return to Okinawa, to load troops for occupation duty in Japan.

Each day I exhausted suspenseful hours waiting new of the arrival of a ship to complete my journey to the U.S. One evening a USO entertainment group appeared at the outdoor theater. The classical program presented by the performers was not well respected by this restive, reveling audience, free of restraint; men who had just shed the haunting and persistent fear of the next battle.

A week after my arrival at the transient camp, I was selected to board a troop ship on a course to San Francisco. Now that the war had ended, the ship was able to sail at night with the running lights illuminated, a sight I had never seen. There was a reluctance to display the running lights for fear of Japanese submarines unaware of the war cessation.

|

My journey home to the US was delayed once more by a stop over on Oahu, in the Hawaiian Islands, for one day. The sight of the distinctive landmark, Diamond Head, appeared to emerge from the sea as the distance from the ship to the promontory shortened. The view of Diamond Head always was a comforting sight when returning to Oahu. This trip not unlike voyages in the past that returned me to this gateway, was in my imagination the front door to my home away from home, where I felt safe. Passengers on board the vessel were not permitted to go ashore. I was disappointed, as Honolulu was the only city, where I felt at ease while in the Army. When the ship set sail, and we departed the mooring, I felt sad, by not unhappy as I was going home.

Departing Pearl Harbor began increasingly anxious days for my travel companions and myself, awaiting the sight of the bay and bridges, the gateway to San Francisco and the U.S. The sights would have to wait a short while, for when the ship arrived at the threshold to the Bay, a thick fog blanketed the harbor. The ship arrival was delayed for most of that day. The pilot boat arrived in the late afternoon included many greeters, the ship was permitted to proceed to dockside. We were welcomed home by a large number of cheering people, carrying flags and banners. An Army Band played patriotic music to make this welcome a memorable event. This was indeed one of my finest hours in the service.

My travel companions and I boarded a ferryboat at the dockside that transported us to Fort McDonnell, located on island in San Francisco Bay where we were billeted and processed before being dispersed throughout the country. Before leaving this camp we were generously fed foods of our choice, a privilege I had never received in the Army. I called my mother at home in Chicago telling her of my arrival, and that I would be home in a few days. Once more I boarded a troop train that returned me to a familiar sight, the railroad yard in Fort Sheridan from where this odyssey began, over thirty three exciting months ago.